The origin of the restaurant name NARO is two-fold. First, the name is an homage to NARO-1, South Korea’s first-ever space vehicle to successfully achieve Earth’s orbit. Second, it is a reference to the Korean phrase “나로 (nah-ro),” “나로 인해서,” meaning “through me.”

Through us – our team, our community, our culture and cuisine – NARO hopes to share the story of Korea’s thousands-year traditions through Hansik, traditional Korean cuisine. Through us, we hope to show the world the beautiful history and bright future of Hansik, to preserve the roots of Korean history, our ancestors’ wisdom and knowledge, and to pass it on to future generations, to be a part of its ongoing evolution.

NARO focuses on more subtle delicate flavors, highlighting traditional techniques with seasonal ingredients, drawing inspiration from classic dishes from various moments of Korean history. Each course of our ever-evolving tasting menus is thoughtfully designed to provide a glimpse of the rich yet delicate beauty of Hansik.

Gim Bugak

Yubu, Ginger, Korean Spinach

Gim is the Korean word for green laver, oftentimes referred to by its Japanese name, nori.

Bugak is a traditional technique in Korea where vegetables are brushed with sweet glutinous rice paste, dehydrated, and then fried. This technique dates back hundreds of years to Korean Buddhist temple cuisine, during the Silla Dynasty in the 6th Century. The technique developed as a way to preserve fresh produce for cold winter months, during times of scarcity.

Gim bugak is one of the most common versions of bugak. It is still a snack enjoyed all throughout Korea today. NARO’s gim bugak is served alongside a yubu, tofu skin, salad, tofu puree, finished with chiffonade Korean spinach.

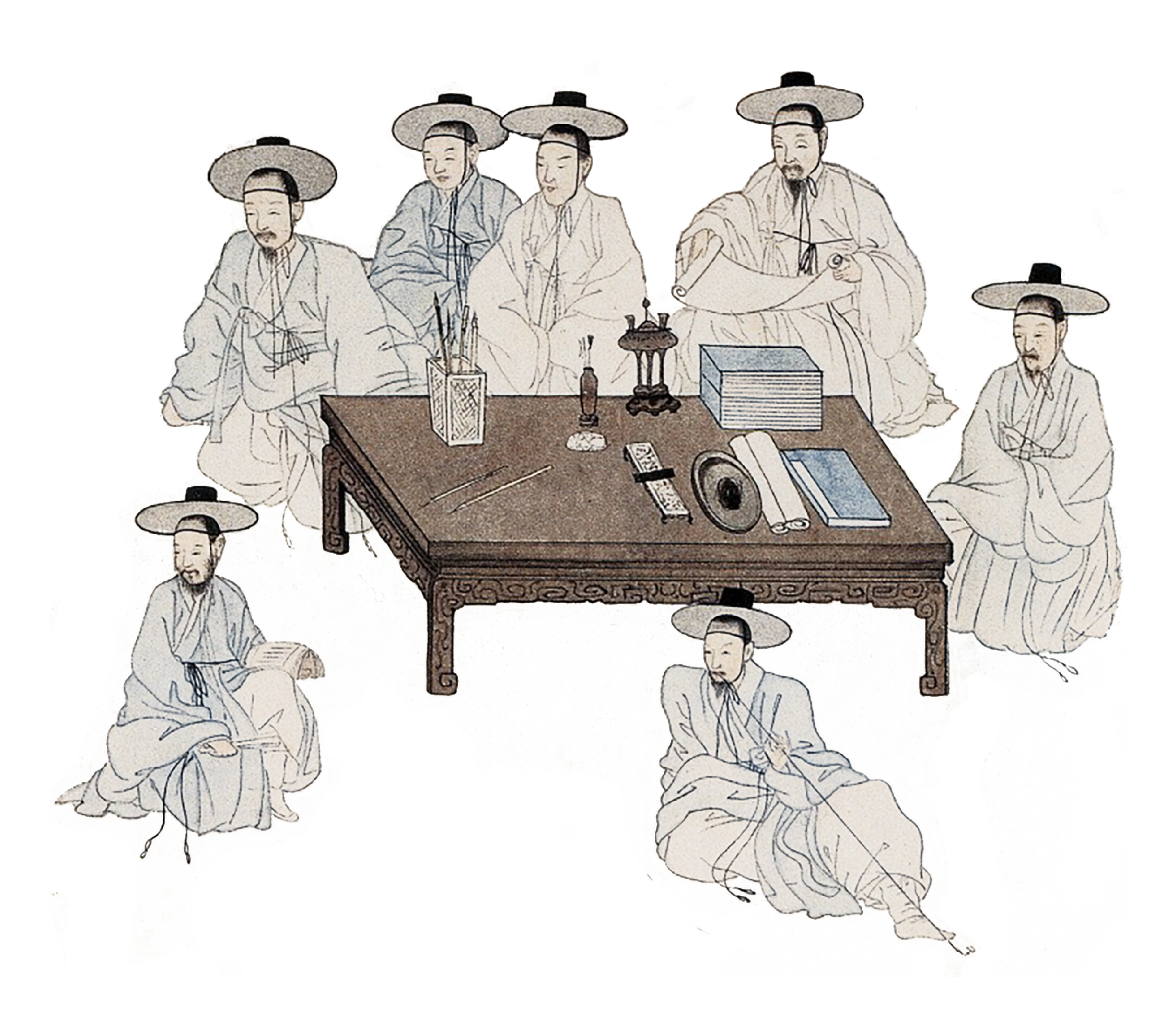

Tangpyeongchae is a Korean salad consisting of mung bean muk, jelly, and a variety of thinly sliced vegetables. It is one of the most quintessential dishes of the Joseon Dynasty. This dish was created by King Yeongjo as a way to symbolize his tangpyeong policy which translates loosely to ‘equity and harmony’.

During King Yeongjo’s reign, fractures in leadership and strife amongst conflicting political factions jeopardized the stability and unity of the kingdom. In order to bring his people together, he led without party bias or affiliation, stressing the importance of working together for a greater good. To symbolize this political ideology of tangpyeong, the tangpyeongchae dish was created and introduced at a grand feast with new leaders. The components of this dish – so different in appearance, color, texture, and flavor – represented diversity yet achieved beautiful harmony.. The symbolism of the dish resonated deeply, a delivered renewed commitment to unity.

NARO’s tangpyeongchae features mung bean muk, egg jidan, thinly sliced strips of egg, and is dusted with gamtae seaweed powder, mung bean sprouts, chives, celtuce, green radish, and kohlrabi, all dressed in a choganjang dressing, essentially a mixture of rice vinegar and soy sauce.

Tangpyeongchae

Mung Bean Jelly, Chilled Vegetables, Choganjang

Potato Jeon

Miyeok, Yuja, Gamtae

Jeon is a catchall term for fritters in Hansik. Jeon, shortened from its original name of jeonyuhwa, dates back to sura, the main royal court cuisine of the Joseon Dynasty.

There are dozens of variations found all throughout the different regions of Korea, as well as throughout Korea’s history, but typically features fish, meat or vegetables that are coated in wheat flour and egg wash, before being pan fried.

Our version features grated potato that has been shaped together before being pan fried. It is then topped with a pine nut emulsion as well as pickled wood ear mushroom and gold bar squash muchim - highlighting traditional Korean cuisine’s highly seasonal approach through a modern lens. The subtle sweetness of the squash intermingling beautifully with the ganjang and sesame oil seasoning; and the creamy texture of the flesh of the squash serving as a delicate contrast to crispiness of the potato jeon.

Shiso Twigim & Lotus Root

Korean Mustard, Eggplant

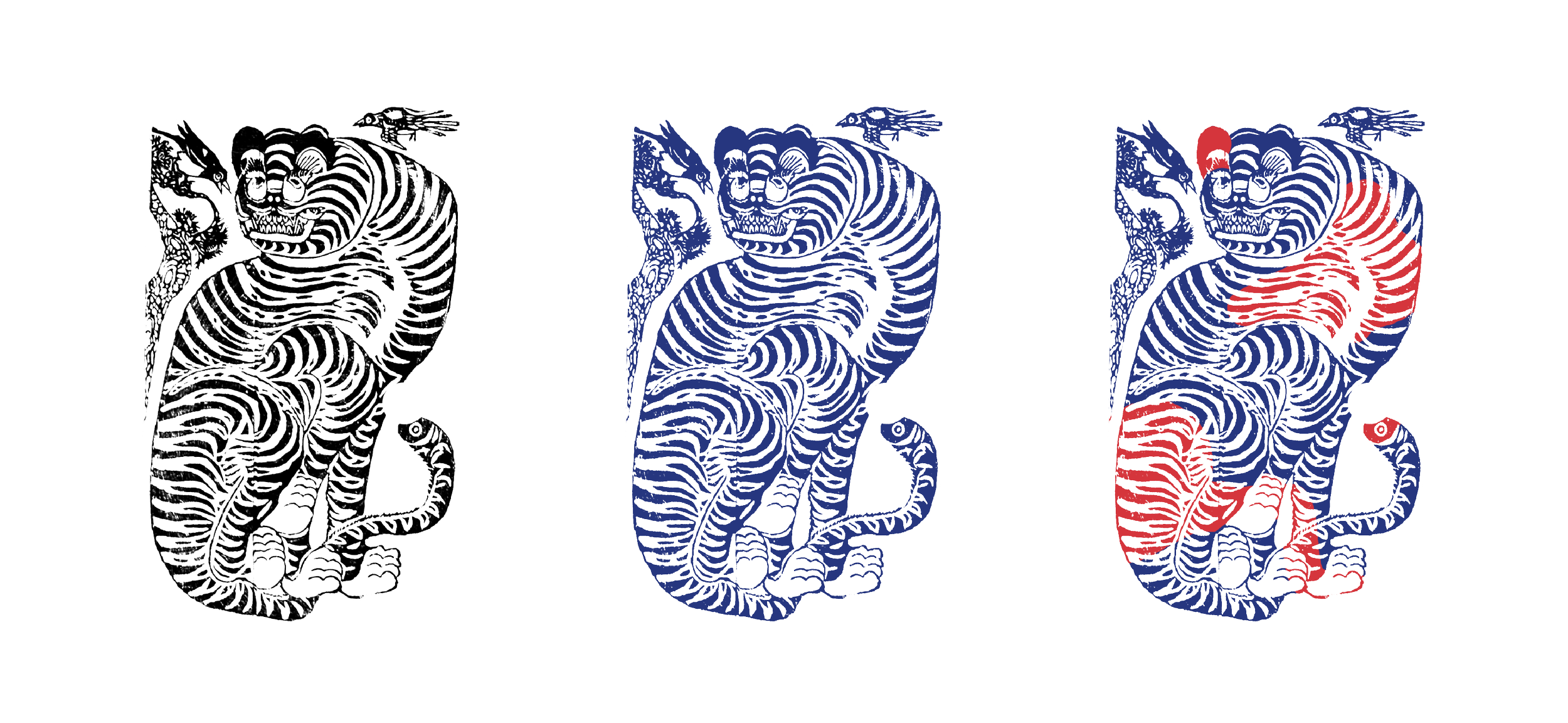

Yachae twigim is a type of dish in Korea that translates to fried vegetables. Whether it be squash, sweet potatoes, scallions, or any other type of vegetable, these light, airy, crispy, fried morsels are enjoyed all throughout Korea - as a childhood favorite after-school snack to a perfect pairing to go along with a refreshing glass after a long day of work. Yachae twigim though, traces its roots back to Korean Buddhist temple cuisine. This is where we first see records of various preparations of fried vegetables being consumed by the masses (and over time, these preparations have evolved into the yachae twigim dishes we know and love today). Our version features fried shiso leaves, served alongside soy-braised lotus root and charred eggplant.

Eungi is a traditional starchy broth, similar to porridge. Records of this dish date back to 1078 AD when yulmu (also known as Job’s tears) was brought over from Song Dynasty China, and was first cultivated on the Korean peninsula.

Similar to how oatmeal is enjoyed all throughout the Western world, eungi served as a relatively easy-to-make early morning meal, packed with all sorts of health benefits (including reducing inflammation and maintaining overall gastrointestinal health). Over time, eungi began to be made with other grains and vegetables, but the most common form of eungi in modern days features chikgaru (or arrowroot starch).

Our version features tomato broth, thickened with chikgaru and is served along with kalguksu (traditional knife cut noodles). On top of the noodles is a stack of siraegi, or dried mu radish leaves, which have been simmered in soy sauce, doenjang, and perilla seed oil. Finally this dish is finished fresh slices of heirloom tomatoes and perilla seed powder.

Tomato Eungi

Kalguksu, Siraegi, Perilla Seed

In Korean cuisine, gui is a grilled dish. Although, most often associated with grilled meat dishes, records have shown vegetable gui over live fire and charcoal just as long as there are records of grilled meat dishes - tracing back to the ancient Yemaek people, a tribal group dating back to 12th to 10th century BC, of the northern Korean Peninsula and Manchuria, regarded by many scholars as the ancestors of modern Koreans.

In this preparation, the lotus root is braised in soy sauce, before it is roasted, scored, grilled, and glazed - developing a texture similar to the crispy skin and tender meat of a roast duck breast.

Our version also features roasted wood ear mushrooms, a sesame and pine nut sauce, and minari. Minari is an herb commonly used in Korean cuisine with leafy greens thicker crisp stems (sometimes referred to as water dropwort or Japanese parsley), but perhaps is most enjoyed as a classic pairing to grilled duck preparations near the city of Gwangju in the southwestern tip of Korea.

Lotus Root Gui

Minari, Wood Ear Mushroom, Sesame

Chamoe Hwachae

Watermelon Meringue, Chamoe Ice Cream

Chamoe (sometimes referred to as a Korean melon or Oriental melon) is the unofficial marker that Summer has arrived in Korea. With a short harvesting season from late June through the end of August, it is the representative fruit of Summer in Korea. Although it is considerably less sweet than most Western varieties of melon (sometimes being compared to as a cross between a honeydew melon and a cucumber), its refreshing quality makes it a ubiquitous treat during the long, hot days of Summer.

With this version, we draw inspiration from a classic Korean beverage called hwachae, a crisp punch enjoyed during the summertime. Records of hwachae date back to 1829, with the first version featuring: rose, azalea, cherries, raspberries, omija tea, honey. Nowadays, the format has evolved to feature all sorts of different fruits, flowers, sweeteners, and bases (even sometimes Sprite, milk, or even soju), but it serves the same refreshing purpose it always has.

Our rendition features pickled chamoe, compressed watermelon, chamoe ice cream, and is finished with watermelon meringue and watermelon juice.

Ganjang is the Korean word for soy sauce, but actually literally translates to “seasoning sauce.” Much like how salt is used in Western cuisine to season food, soy sauce has been traditionally used in Korean cooking to season dishes.

Although most commonly used in savory applications, ganjang, much like salt, can find its way into both savory and sweet dishes. This dish presents the continued evolution of the use of ganjang within Korean cuisine, playing off of the deep flavors of ganjang to balance elegantly with the creamy barley mousse, the boldness of the pralines, and the richness of the chocolate cake.

Ganjang Pecan

Chocolate Ganjang Cake, Pecan Praline, Coffee Ice Cream